“Maryland is #1 in education” is a claim frequently made by Maryland elected officials, yet the frequent chest bumps were called into question again when it was discovered that the state had cheated on national reading tests. The Maryland schools cheating scandal is receiving a lot of attention as we are force to reconsider all the claims made by state education leaders.

“Maryland is #1 in education” is a claim frequently made by Maryland elected officials, yet the frequent chest bumps were called into question again when it was discovered that the state had cheated on national reading tests. The Maryland schools cheating scandal is receiving a lot of attention as we are force to reconsider all the claims made by state education leaders.

When Maryland officials recently bragged about the performance of their students on the 2013 National Assessment of Educational Progress, they failed to mention that the state blocked more than half of its students that had learning disabilities or were non-native speakers from taking the test.

Maryland removed challenged students at rates more than five times the national average, and more than double the rate of any other state. If the excluded students were included it is estimated that Maryland would drop from 2nd place in fourth-grade reading to 11th place; In eighth grade reading the state would fall from 6th to 12th place.

______________________________________________________________

GOP Gubernatorial Hopeful Ron George Calls For Hearings On Maryland Reading Scores

By John Wagner, Washington Post, November 27, 2013

Maryland Del. Ronald A. George, a Republican candidate for governor, called Tuesday for legislative hearings on why Maryland excluded an unusually large number of English language learners and students with learning disabilities from taking a national reading test.

George (R-Anne Arundel), who sits on a House education subcommittee, accused the administration of Gov. Martin O’Malley (D) of being involved in a “cheating scandal” intended to make the state’s performance look better. If a greater number of students had taken the 2013 National Assessment of Educational Progress, Maryland’s rankings would have been lower, as The Post reported this week.

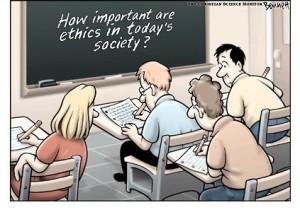

“We tell our students cheating is wrong and hold them accountable when they make a mistake,” George said. “What message are we sending them now when corrupt politicians abuse the education system to advance their own political agendas?”

O’Malley spokeswoman Nina Smith said that “some people are so desperate to score political points that they’re willing to question the achievements of our students and educators.”

Smith noted that Education Week magazine had ranked Maryland schools No. 1 for five years in a row and said that the NAEP scores in question were only “a small part” of what went into the ranking.

There was no immediate response Tuesday from Democratic legislative leaders to George’s request. Democrats hold commanding majorities in both the Maryland House and Senate.

Maryland excluded 62 percent of students in two categories — learning-disabled and English learners — from the fourth-grade reading test and 60 percent of those students from the eighth-grade reading test. Those rates were five times the national average and more than double the rate of any other state.

Lillian Lowery, the state’s superintendent of schools, told The Post that she plans to review the state’s exclusion rates and their effect on the state’s test performance.

Democratic gubernatorial hopeful Douglas F. Gansler also weighed in Tuesday on the controversy over the test scores.

“The parents of Maryland deserve honest and transparent testing – and a more thorough explanation of how they were misled by a system that appears to have put a blind desire to pump up scores ahead of the needs of Maryland families,” Gansler, the state’s attorney general, said in a statement.

The Post reported this week that the National Center on Education Statistics, the research arm of the U.S. Department of Education, estimated how every state would have performed on the reading test if it had included those with learning disabilities and English language learners. For most states, the change would have resulted in a point or two difference in average scores on the test, which is graded on a point scale from zero to 500.

If Maryland had included its learning-disabled and English learners, the state’s average score would have dropped approximately eight points — from 232.1 to 224.5 — for fourth-grade reading and about five points — from 273.8 to 269 points — for eighth-grade reading. That estimated change would drop Maryland from having the second-highest state score in fourth-grade reading to 11th place; Maryland would fall from sixth place in eighth-grade reading to 12th place.

George is in a competitive Republican primary next year against Harford County Executive David R. Craig; Charles County businessman Charles Lollar; and Larry Hogan, an Anne Arundel County real estate broker and Cabinet secretary under former governor Robert L. Ehrlich Jr. (R).

Gansler faces Lt. Gov. Anthony G. Brown and Del. Heather R. Mizeur (Montgomery) in next year’s Democratic primary.

______________________________________________________________

National Association Of Education Progress Test Scores*

Frederick News Post, November 27, 2013

As Mark Twain famously observed way back in 1906, “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.”

We’re not suggesting in this editorial that anything like that occurred with Maryland’s scores on the 2013 National Assessment of Educational Progress test, but read on.

There appears to be a fair amount of confusion and skepticism in the public mind surrounding educational “assessment” in general. What do all these tests really measure? What is the significance of rankings? Are schools too focused on “teaching to the test”?

Now we learn that Maryland’s scores and national placement on the 2013 NAEP test are skewed. The reasons why raise a few questions about both this national test and reading education in Maryland.

As with all such tests, we assume that NAEP results are supposed to indicate how well a state such as Maryland is doing in teaching subject matter — in this case, reading — and how it stacks up against other states.

A recent Associated Press story, however, reported that Maryland had excluded a significant percentage of students in two key categories from taking the test — English language learners and students with learning disabilities. Obviously, this bumped up the state’s scores and national placement.

In fact, Maryland blocked 62 percent of fourth-graders and 60 percent of eighth-graders in these two categories from taking the NAEP test.

According to the AP story, Maryland’s exclusion rate was “more than double that of any other state” taking the test.

The story went on to report that “The governing board overseeing the test has set a goal that states exclude just 15 percent of learning-disabled and English language learners.”

“Set a goal”? What does that mean? Apparently nothing, since Maryland’s exclusion rate was four times that high.

How is the state Board of Education explaining all this? This way: Maryland accommodates learning-disabled students on yearly exams by permitting the text to be read to them by a person or computer, as opposed to requiring them to read it themselves. And since NAEP doesn’t permit this read-aloud accommodation during its annual test, those students were excluded from taking it. Voila!

Where to start? First of all, if NAEP results, especially comparative ones, are to mean anything, every state must be playing under the same rules. Clearly that was not the case in the 2013 test. Second, how and to what extent does reading test material aloud to students, in lieu of their reading it themselves, actually measure their reading ability?

What’s the verdict of Maryland’s 2013 NAEP scores and comparative ranking? Referring to the Maryland exclusion percentage, Lindsay Jones, of the National Center for Learning Disabilities, says, “That number is a red flag. It stands out this year in particular because NAEP’s (average) exclusion rate has dropped so much.”

Clayton Best, who is NAEP’s Maryland coordinator, says he’s concerned about “the implication that this is a conscious process to eliminate students taking the test to improve the NAEP scores. There is no motivation to do that at all.”

Let’s say that’s true. But even so, it doesn’t change the fact that Maryland’s scores on this test, and its ranking among the other states, require asterisks.

Sorry, Maryland, but the chest bumps and bragging rights will have to wait for another day. Meanwhile, NAEP needs to issue some specific new rules as to exactly who must take this test — and dump the nonbinding “goals.”

______________________________________________________________

Maryland Test Exclusion Rate Raises Questions

By Lyndsey Layton, Washington Post, November 24, 2013

When Maryland officials recently trumpeted the performance of their students on national reading tests, they failed to mention one thing: The state blocked more than half its English language learners and students with learning disabilities from taking the test, students whose scores would have dragged down the results.

Maryland excluded 62 percent of students in two categories — learning-disabled and English learners — from the fourth-grade reading test and 60 percent of those students from the eighth-grade reading test.

The state led the nation in excluding students on the 2013 National Assessment of Educational Progress, posting rates that were five times the national average and more than double the rate of any other state.

Lillian Lowery, the state’s superintendent of schools, said she plans to review the state’s exclusion rates and their effect on the state’s test performance.

“We do need for those students to be included, absolutely,” Lowery said. “We want parents and students to know exactly how they are performing, as it relates to what they’ve been able to do, and that they’re ready to graduate from high school [being] college- and career-ready. It is certainly data that we need to unpack and review.”

Maryland’s percentage of excluded students is also notable because it has been increasing during the past decade, while every other state has moved in the opposite direction.

The governing board that administers the test has been encouraging states to include as many students as possible and set a goal that they exclude just 15 percent of learning-disabled and English language learners.

“States that opt out the largest percentages of students on NAEP tend to end up with higher scores relative to other states; so parents in Maryland may be misled as to how well their schools are doing compared to other states around the country,” said Timothy Shanahan, a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago, who is an expert in reading and reading tests.

The National Center on Education Statistics, the research arm of the U.S. Department of Education, estimated how every state would have performed on the reading test if it had included those with learning disabilities and English language learners. For most states, the change would have resulted in a point or two difference in average scores on the test, which is graded on a point scale from zero to 500.

If Maryland had included its learning-disabled and English learners, the state’s average score would have dropped approximately eight points — from 232.1 to 224.5 — for fourth-grade reading and about five points — from 273.8 to 269 points — for eighth-grade reading. That estimated change would drop Maryland from having the second-highest state score in fourth-grade reading to 11th place; Maryland would fall from sixth place in eighth-grade reading to 12th place.

Clayton Best, Maryland’s NAEP coordinator, said the state excludes so many students because it offers an accommodation known as “read aloud” to learning-disabled students on annual state exams. When a read-aloud accommodation is made, a person or a computer reads the text to the student.

If a learning-disabled student uses read-aloud, it is likely included in a legally binding agreement between the student and the local school district — known as an individualized education plan — that spells out the kinds of accommodation a student will receive in the classroom and on tests.

Because NAEP does not permit the read-aloud accommodation, Maryland can exclude such students. The Maryland Department of Education first decided to offer the read-aloud accommodation in 1991.

“What concerns me is the implication that this is a conscious process to eliminate students taking the test to improve the NAEP scores,” Best said. “There’s no motivation to do that at all.”

Fewer than 10 states permit the read-aloud accommodation, which is controversial within the community of people with disabilities. Some think it is an important tool to help people with severe learning disabilities engage with the written word. While having a passage read aloud removes the decoding aspect of reading, the student still has to make sense of the passage, so it still tests comprehension, they say.

Others think the read-aloud accommodation defeats the purpose of a reading test.

“You no longer have a reading test. Now you have a listening test,” said Richard Allington, a professor of education at the University of Tennessee and an expert on early literacy. The accommodation “allows special-education teachers, classroom teachers and the school to avoid the responsibility of actually teaching those kids to read.”

But even advocates for people with disabilities who support the use of the read-aloud accommodation question why Maryland’s exclusion rate is so high.

“That number is a red flag. It stands out this year in particular because NAEP’s (average) exclusion rate has dropped so much,” said Lindsay Jones, the director of public policy and advocacy for the National Center for Learning Disabilities. “It’s a cause for further examination, absolutely.”